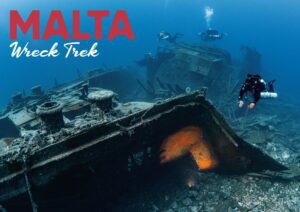

Scapa Flow, widely regarded as one of the world’s best wreck-diving sites, should be on every diver’s hit-list, as dedicated fan Mark Evans reports

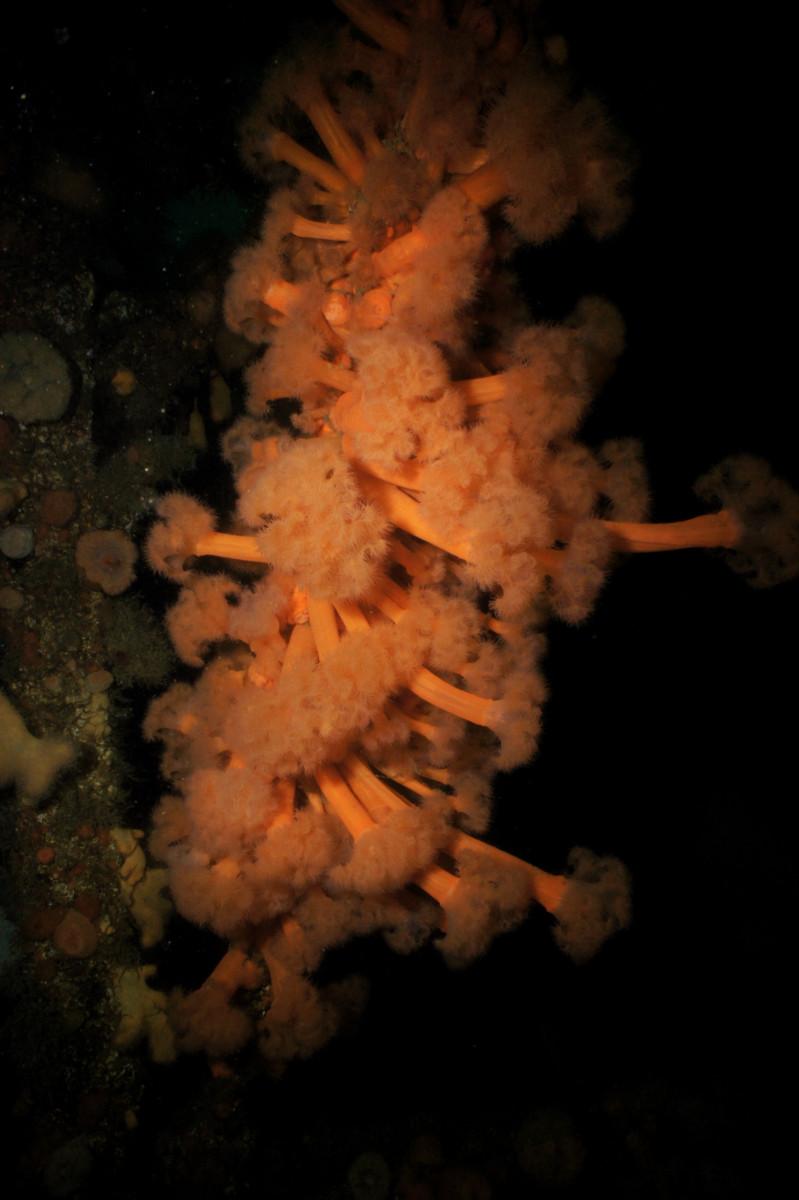

Arriving at the bottom of the shotline, which was festooned with gigantic plumose anemones, the side of the silt-covered battleship just dropped off into darkness in front of us. Switching on our torches, we descended into the gloom, watching the metres rise steadily on our dive computers until the seabed loomed into view at 38m. What looked like a cave opened ominously before us, and we carefully ventured in, keeping our movements as gentle as possible to avoid causing a silt explosion.

A wall of steel rose up, and after a couple of moments our narcosis-addled brains realised this was the side of an upturned main gun turret. Heading left towards the bow of the Kronprinz Wilhelm, the barrel protruded from the turret and just seemed to go on forever. Even half-buried in the silt, the diameter of the barrel looked enormous, and we took some photographs with divers alongside to show how large these 12-inch monsters really were. Throughout all this, I tried not to think that I was underneath an upturned, 26,000-tonne German battleship that had been on the seabed for 97 years…

Scapa Flow

The virtually landlocked natural harbour that is Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands is one of those places that many divers have heard of and long to visit, but only relatively few experience, which is a huge shame when this hotspot genuinely should be on the hit-list of every diver. I’ve made several pilgrimages up to the very northern tip of Scotland to explore this wreck-diving Mecca, which is right up there with Truk Lagoon and Bikini Atoll, thanks to the remains of monstrous German warships from World War One lying on the seabed.

There are various reasons why this place is not jam-packed with thousands of divers – one, it is a long old trip from just about anyway in the UK and when costs end up being similar to a Red Sea liveaboard, often the tropical destination wins hands down; and two, Scapa has an undeserved reputation for being deep, cold, dark and dangerous and only suitable for highly trained techies, when in fact any Advanced Open Water Diver comfortable in a drysuit and with their Deep Specialty is more than qualified enough to dive the main wrecks (there are also plenty of sites suitable for Open Water Divers as well).

In fact, on previous trips I have taken divers up to Scapa who had never dived in UK seawater before, only inland sites, and they went on every dive the more-experienced divers in the party did.

As for the cost – yes, it is relatively expensive (as far as UK diving goes) once you factor in fuel costs, ferry charges, accommodation, boat charter, nitrox fills and food and drink, but the diving available is like nowhere else on the planet and it really is one of those places that all divers should experience. But believe me, you might think the one visit will be enough to ‘tick the box’, but most people I know well and truly catch the Scapa bug and can’t wait to come back.

The High Seas Fleet

Scapa Flow probably wouldn’t really factor on any ‘must-dive’ list if it wasn’t for the actions of a certain Rear Admiral Ludwig von Reuter. He was the commander of the German Imperial Navy’s High Seas Fleet, which was interned in the Flow with weapons disarmed and just skeleton crews on duty. On midsummer’s day on 21 June 1919, he mistakenly believed that hostilities were about to resume and gave the signal to scuttle the entire fleet of 74 warships, comprising five battlecruisers, 11 battleships, eight cruisers and 50 destroyers.

A total of 52 of the great ships sank beneath the surface, the remaining 22 were beached or prevented from being sunk by Royal Navy boarding parties. Now, with all that intact metal on the seabed, including the huge 200-metre battlecruisers Seydlitz, Moltke, Von Der Tann, Derfflinger and Hindenburg, you can imagine what sort of scene wreck divers can witness underwater today.

Right? Wrong. Sadly for divers, what followed from the early 1920s right up to 1946 was what is still the greatest marine salvage operation in history. The firm of Cox and Danks raised, towed and dismantled no less than 45 of the sunken vessels, and the remaining seven – battleships Konig, Kronprinz Wilhelm and Markgraf, cruisers Dresden, Coln and Karlsruhe, and mine-layer Brummer – were left in various states of disrepair after some further salvage and blasting work by other parties.

Thankfully, German craftsmanship back then was as good as it is now, and so while the Karlsruhe, Konig and, to a lesser extent, the Brummer are deteriorating rapidly from a recognisable ‘ship-shape’, the other ships – in particular the Coln – are holding up pretty well considering they are only three years away from celebrating 100 years underwater! You can still see the teak decking, 5.7-inch deck guns, capstans, bollards, armoured conning towers and much more on the cruisers, and the big 12-inch turrets, massive rudders and a last-remaining impressive bow across the three battleships.

Coated with a thick layer of silt and draped with sponges, plumose anemones and dead man’s fingers, it can sometimes be hard to make sense of certain objects, but get your brain orientated as the ship lies – on its side for the cruisers and mine-layer, upside down for the battleships – and you can soon build up a picture of what it must have looked like pre-sinking. The sheer size of the ships is daunting, but concentrate on one area – like bow to midships, for example – and you will be able to really enjoy what the wrecks have to offer.

Diving the Flow

There are several dive charter boats operating in Scapa Flow, ranging from large fishing boats-cum-liveaboards to smaller dayboats, and most cater for everyone from raw novices making their first foray into the Flow to seasoned techies emblazoned with CCRs, sling-tanks and other nifty paraphernalia. On my last trip we were diving from the purpose-built MV Huskyan, expertly skippered by Emily Turton (see box out).

We had a mixed group of CCR, twinset and single-cylinder divers on board, and all agreed that they wanted to concentrate on the seven German warships. Although this meant missing out on diving the purpose-sunk blockships, or the World War Two vessel F2, it is the best way to get the most out of the ‘main event’ – with two dives a day for six days, it enables you to get two ‘hits’ on most of the German wrecks and really get a feel for them.

Diving the German fleet is a doddle. The skipper tells you when you are 15 minutes out from the site and you get into your kit. Once over the wreck, you stand near the exit point and the skipper will motor close to the buoys marking the shotline. On their command, you leap into the water, head over to the line and then make your descent to the wreck.

Once on the wreck you can either go off exploring and then just fire up a DSMB for your ascent or you can make a circular route and use the shotline for reference on the ascent. There is generally not too much current on the ‘big seven’, and visibility is generally anywhere from three to nine metres – we were blessed with good vis of seven or eight metres plus on virtually every German wreck dive during our week in May – unless you hit the dreaded plankton bloom.

Scapa Flow deserves its reputation as one of the best wreck-diving locations in the world – where else can you dive seven World War One German warships in depths of less than 46m? – and as explained earlier, don’t be put off by the macho bull often heard when people talk about diving in the Orkneys.

To get the most out of the German wrecks, just make sure you are comfortable in your drysuit, don’t mind dropping down shotlines in relatively low vis and have your Deep Specialty. The diving isn’t hard, but you do need to treat the wrecks with respect – they are still in remarkable shape considering the length of time they’ve been on the seabed, but they are covered in a fine layer of silt, and certain parts are collapsing, so only do any penetration if you are fully trained and have the appropriate equipment to do so.

Having dived the High Seas Fleet many times in the last 20-odd years, I did notice some major changes to certain wrecks this time around. The cruiser Dresden, for instance, offers a whole new dive experience around the bow section, as a huge area of the decking is peeling away and is now almost down to seabed level, revealing previously unseen rooms, passageways and ladders. The mine-layer Brummer is fairing even worse, with various areas now becoming increasingly unstable. At the bow, huge sections of the forward hull have now rusted away, leaving just the scythe-like bow intact.

Having said that, to say that the ships have been lying on the bottom of Scapa Flow for 97 years, they are still holding together remarkably well in the main. Yes, the Dresden, and the Brummer in particular, are slowly succumbing, but the Coln still looked pretty much the same as when I last dived her, and I even got to see some stuff I’d never spotted before thanks to skipper Emily’s ultra-detailed briefings.

Elsewhere, thing were also much the same – dropping to 37m on the Kronprinz Wilhelm and venturing beneath her vast hull to see the barrels of her main gun turrets, I had a serious case of déjà vu, the scene was so familiar. Long-time Scapa divers will still find much to keep them entertained, and the slow decline of the shipwrecks is continually opening up new areas for exploration, while Scapa virgins will just be blown away by the sheer size of the vessels.

The shipwrecks offer a multitude of subjects for avid photographers, from the main gun turrets and deck guns to conning towers, windlasses, anchors, torpedoes and, of course, the actual vessel’s themselves, particular bows and sterns.

Getting to the Orkneys

As mentioned earlier, the Orkneys are a long way from just about anyway in the UK, but there are several ways to get there:

You can drive all the way up to Scrabster on the northern-most tip of mainland Scotland and then catch a ferry to Stromness, which is where all of the dive charters operate from. However, this involves a lengthy drive, the last section of which is on the A9, which is scenic but not exactly the quickest road!

You can drive to Aberdeen and catch a ferry with Northlink Ferries (www.northlinkferries.com) that sails up to Kirkwall, and from here it is just a 20-minute drive to Stromness. The ferry journey from Aberdeen to Kirkwall takes some six hours, but you can relax, enjoy some food and even watch a movie in the on-board cinema.

You can fly to Aberdeen, and then get a hopper flight to Kirkwall, but flights are not cheap – particularly the latter part of the journey – and if you decide to take your kit with you, excess baggage fees could get enormous!

PREFERRED PARTNER the MV Huskyan

The MV Huskyan is a purpose-built steel and aluminium dive boat with a square stern to maximise space for the dive deck, a handy crane to assist with loading and unloading kit, twin engines for super manoeuvrability and redundancy, a large diver lift for easy water exit, and a wet changing area fitted out with drysuit hangers, and hooks for your gloves and hood.

Inside, divers are treated to two metres plus of headroom throughout and what can only be described as a luxury interior, which includes massive galley – serving up delicious home-made grub between dives and on the way back to the harbour at the end of the day – and spacious dining/sitting/briefing area, plus downstairs a dry changing room complete with multiple lockers. Skipper Emily Turton’s briefings are legendary, as she has an intimate knowledge of the wrecks through diving them herself extensively, and now she has added further technology that allows her to ‘draw’ on the ADUS 3D scans and her own sketches of the sites, which is then displayed on two large flatscreen TVs.

Emily can offer the complete diving-and-accommodation package, with superb self-catering facilities available in Number 15, an impeccably presented house with multiple bedrooms/bathrooms, massive kitchen, wifi, flatscreen TV and more.

Check out the websites: www.huskyan.com and www.number15orkney.com

Photographs by Mark Evans and Jason Brown